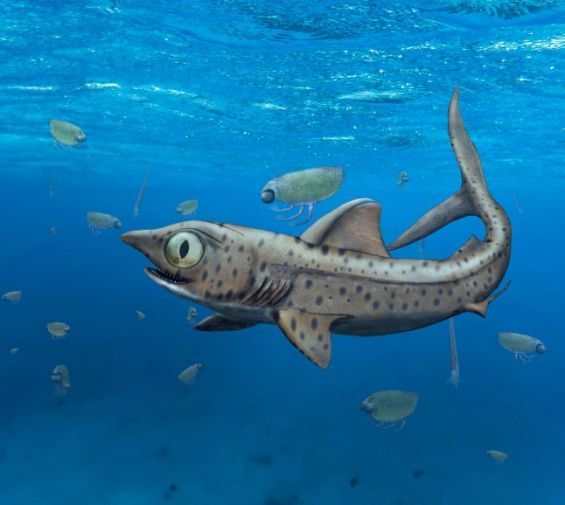

Ancient sharks that lived 300 to 400 million years ago had a unique jaw mechanism, researchers found after analyzing fossils found in Morocco.

Studying the jaw construction of a symmoriiform shark, Ferromirum oukherbouchi, from the Late Devonian of the Anti-Atlas, Paleontologists at the University of Zurich, the University of Chicago and the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden revealed significant details about the way modern sharks’ ancestors used to prey.

According to a study published this week, the animals were able to drop their lower jaws downward when preying. Analyzing the way their jaws functioned, researchers found out that these sea monsters used to rotate their lower jaws outward when opening their mouths to get their teeth to catch more of their prey.

Using CT scanning and 3-D printing of the jaw remains found in Morocco, researchers also discovered that unlike their predecessors, prehistoric sharks had teeth that were replaced slowly and when their mouth closed, smaller older and worn out teeth stood upright on the jaw while younger and larger ones pointed toward the tongue and were invisible when the mouth closed.

Analyzing the jaw of Morocco's Ferromirum oukherbouchi

The findings were based on the examination of the 370-million-year-old jaw of Morocco’s Ferromirum oukherbouchi. The team used computed tomography scans, reconstructed the jaw and printed it out as a 3-D model. This technique helped simulate and test the mechanism of the jaw.

Said simulations showed that unlike humans, said shark did not have the «two sides of the lower jaw fused in the middle». This helped the animal freely rotate the jaw outward.

«Through this rotation, the younger, larger and sharper teeth, which usually pointed toward the inside of the mouth, were brought into an upright position. This made it easier for animals to impale their prey», first author of the study Linda Frey explained. «Through an inward rotation, the teeth then pushed the prey deeper into the buccal space when the jaws closed», she added.

In addition to rotation, the shark’s unique jaw mechanism allowed it to engage in suction-feeding, a method of ingesting a prey item in fluids by sucking the prey into the predator's mouth.

«In combination with the outward movement, the opening of the jaws causes sea water to rush into the oral cavity, while closing them results in a mechanical pull that entraps and immobilizes the prey», the study revealed.

«The excellently preserved fossil we've examined is a unique specimen», says UZH paleontologist and last author Christian Klug, who believes that the discovery shows how important the role this mechanism played in the Paleozoic era, which began with the breakup of one supercontinent and the formation of another.

chargement...

chargement...