Present for more than 2,000 years in North Africa, the Jewish community is a significant component of the region’s history. In Morocco, Jews have expressed their attachment to the Monarchy, especially under the Protectorate (1912 – 1956) as they joined resistance movements against the French.

Moroccan Jews have, indeed, forged a special relationship with the Kingdom’s leaders during the 20th century, starting with Sultan Mohammed Ben Youssef, who later became King Mohammed V (1927 – 1961), then King Hassan II (1961 – 1999). This special relationship was reinforced thanks to the Sultan, who helped protect the Jewish community during the Holocaust by refusing to hand them over to the Nazi-allied Vichy regime (1940 – 1944).

The massive departure in the 1940s

The political move gave a sacred aura to the relationship. There are many citizens of Jewish faith from Morocco who «pray at the tombs of Mohammed V and Hassan II in their Mausoleum in Rabat», ritualizing the practice «with gestures that resemble the ones of pilgrimages performed on the tombs of Jewish saints», wrote academic Emanuela Trevisan-Semi.

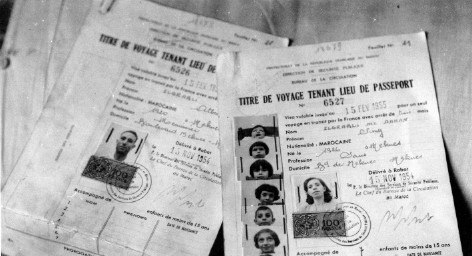

Although the departures started in the 1940s, the Jewish community’s attachment to the King’s figure has remained intergenerational. The number of Moroccan Jews leaving the country increased with the adoption of the partition plan for Palestine in 1947, the creation of the State of Israel in 1948 and the independence of Morocco in 1956. Historian Haïm Zafrani recalls these departures, noting that from the end of the 1940s, «we witnessed the break-up of the community and the emigration of almost all of its populations».

«Out of the 250,000 individuals who in the 1950s and 1960s populated the mellahs, also cohabited with the Muslims in the medinas of certain cities (…) there are only less than 5,000, mostly concentrated in the economic capital Casablanca», he wrote in «Deux mille ans de vie juive au Maroc» (Eddif - 2000). The book also underlines that while some «groups have chosen France, Canada and Latin America as their host land; the vast majority were directed to the 'promised land' or went there of their own accord».

Emigration to Israel began in 1948 and experienced a first peak between 1954 and 1956, with 70,000 departures. A second wave took place the year King Mohammed V passed away in 1961, then a third one during the reign of King Hassan II in 1963, with 80,000 departures.

But wherever these communities have settled, they have tried to maintain a link with the country where they were born. In «Hassan II et les juifs : histoire d'une émigration secrète» (Le Seuil - 1991), Agnès Bensimon recalls the political and economic climate which «led to a collective flight, in part organized by the Mossad (under cover of a Jewish diasporic association, the Hebrew Immigration Associated Service of New York) through secret agreements and complex negotiations with Hassan II».

This is confirmed by Emanuela Trevisan-Semi, mentioning in 2007 that «the least qualified and poorest sections of the population, as well as the most ideologically motivated, emigrated to Israel». The others, often made up of elites, «settled in France and Canada as they were French-speakers, and in Spain and Latin America for those who spoke Spanish, or even in the United States».

Strengthened links with the Moroccan authorities

Based on statistics released in 2006, the researcher emphasizes that «800,000 Israelis are from Morocco out of a total population of about 6.2 million individuals», around 13% of the country’s population. «156,500 people were born in Morocco, 336,000 were born in Israel to one or two Moroccan parents, the rest forming the third generation», she wrote.

In 1986, a commemorative statue of King Mohammed V was installed in Ashkelon near Tel Aviv. From 2000, sites of memory have multiplied, «formalized by the mayors and 'sacralized' by the special blessings of the great local rabbis». The Hassan II Street was inaugurated, near Rehovot, then «a park in Bet Shemesh, a place in Sderot in the north of the Negev, a place in Petah Tiqva, a park in Ashdod, and a walk in Kyriat Gat». In the same period, a commemorative stamp was issued, in addition to the production of a film and the more frequent organization of evenings in memory of King Hassan II.

According to Emanuela Trevisan-Semi, these initiatives have had the support of Moroccan-Israeli civil society organizations, «in particular an association which federates the Moroccan Jewish diaspora: the World Federation of Moroccan Judaism».

King Hassan II gained a great reputation among Jews after participating in the peace negotiations between Palestine and Israel.

In Israel, the descendants of Moroccan Jews have created new shrines for their dead, imbued with the identity of their country of origin. They also «struggled to transfer some relics of saints whose graves were in Morocco, in order to create new places of worship», according to Emanuela Trevisan-Semi.

The expression of this form of sacralization for Morocco has also been documented among the Moroccan Jewish community settled in North America. A video has recently reappeared on the Internet, showing images of a meeting dating from the 1960s. In said media, King Hassan II was meeting members of the community and exchanging prayers.

chargement...

chargement...