In 1959, shortly after Morocco broke free from the French, hundreds of people started complaining about similar symptoms. While some of them said that they were unable to walk, others felt that both their legs and hands were suddenly paralyzed.

The number of these unfortunate people kept growing, especially in Meknes, a city in central Morocco. The victims doubled, and the sickness that left hundreds of people disabled was a mystery to the Moroccan sanitary authorities.

At first, the sudden and unknown illness and its symptoms looked like a poliovirus outbreak, a virus that spreads from one person to the other, infecting the spinal cord and causing paralysis. But the rapidly growing number of victims and the tests carried out «showed it could not be polio», Canadian journalist Peter Desbarats wrote.

By September 1959, Morocco had recorded more than 300 cases in Meknes only, with other parts of the country, namely Nador and the Rif Mountains, reporting similar cases. Fighting against an unknown enemy, Morocco decided to ask foreign help to curb the spread of the disease and eventually put an end to the health crisis.

An unkown enemy

«Disturbed by the news of the catastrophe, the world was moved to act and governments as well as private agencies sent all they could, both in money and kind», Swiss doctor Ambrosius von Albertini recalled in one of his books. He revealed that «from the beginning of December 1959 vast stocks were being sent to Morocco by air».

In addition to stocks and medical supplies, Morocco needed to know the origins of the outbreak and identify what was behind this sickness affecing thousands of its people. To answer all of these questions, the World Health Organization (WHO) sent Oxford epidemiologists J. M. K. Spalding and Honor Smith.

Investigating the cases and their background, the two doctors quickly realized that the source of the sickness was related to food products. According to Desbarats «one important clue was that the outbreak seemed to be confined to the Moroccan artisan class—meaning people with jobs but jobs with low pay».

A study by the British team indicated that «not one of Morocco's two hundred thousand Jews was afflicted, and the only European in Meknes who had been struck down was a man who had adopted the Arab way of life», stressing that «Jews, Christians and Arabs (Muslims) all eat differently in Morocco».

The team also found out that troops living in barracks and prisoners were not affected. Their conclusions «ruled out the possibility of infection».

Cooking oil with TCP

The two epidemiologists went for the hypothesis of food poisoning, as in, food consumed by the categories affected by the disease. While analyzing foods that could have been poisoned, a Meknes doctor brought Smith and Spalding's attention towards cooking oil.

«He knew of a family that, suspicious of the dark oil, had given some to their dog. When the dog appeared to be all right, they had put the oil into regular use. In a few days, all had been struck by the strange malady—and so had the dog».

Connecting the dots, the team realized that it was all about this dark-colored cooking oil, a monster that was still sold in the city’s ancient medina.

Spalding and Smith hence discovered the culprit behind the catastrophe. It was «a single colored bottle labeled Le Cerf, a brand of cooking oil». After it was sent to the Institute of Hygiene at Rabat, tests «spotted the poison: a yellow, odorless chemical named tri-ortho-cresyl phosphate, one of the family of oils commercially called TCP in North America», the same source added.

The poison, which represented 67% of the bottle of oil, «interferes with the normal process of fat emulsification and absorption and emboli may occur in the central nervous system», read a document entitled «The Results of Intoxication with Orthocresyl Phosphate Absorbed from Contaminated Cooking Oil, as seen in 4,029 Patients in Morocco».

But where did this TCP come from and how did it get into cooking oil ? The answer lied in the US military bases in Morocco. According to the Canadian journalist, when the US was about to leave its air force bases in Morocco, it sold off «many surplus supplies, including TCP-bearing oil» it used for jets.

The oil made it eventually to dealers who mixed it with cooking oil and sold it across the country. By the time the medical team discovered the source of the outbreak, the number of victims was still growing.

Records show that almost 20,000 people were affected by the poisonous oil. To help with the crisis, the World Health Organization and the League of Red Cross Societies were called for assistance in establishing the cause of the illness and treating the victims. The preliminary treatment program was planned by Professor Dennis Leroy of the University of Rennes, France.

A medical team led by Canadians was also sent to Morocco to help with the health crisis. «By the end of February, the Red Cross teams had examined—and begun to treat the most serious cases among—6,300 victims, almost two-thirds of the 10,466 that were to register by the end of the program», Desbarats wrote.

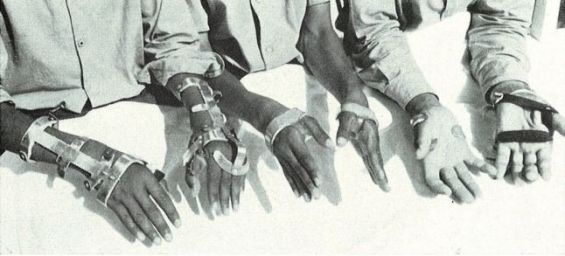

«Sixty percent of the older victims were women» while «sixty percent of the victims had paralysis of the hands as well as feet, and that in fifteen percent paralysis had reached the legs and hips», he added.

By the end of the operation, it was announced that 85 percent of the 10,466 victims had been completely cured. «Only 272 required further treatment after June 30, 1961 and about that many more needed further medication», the same source concluded.

The crisis was finally managed with the help of the WHO and the Red Cross as well as the Moroccan authorities at the time which worked on eliminating the dangerous product from all the markets across the country.

What appeared to be a viral epidemic was in reality massive poisoning from oil. In 1981, Spain experienced a similar tragedy with more than 20,000 victims.

chargement...

chargement...