By the end of the sixteenth century, Saadi sultan Ahmed al-Mansour saw his empire hit by a deadly plague. The first wave of the epidemic struck between 1597 and 1598, disturbing the rule of the powerful sultan.

History records report that Morocco was going through «a series of famines and devastating pestilence that disrupted the latter years of al-Mansur’s reign».

Indeed, while numbers suggested that by 1598 the plague took the lives of at least 450,000 Moroccans, trade was disrupted and the country’s most important ports were shut because of the health crisis.

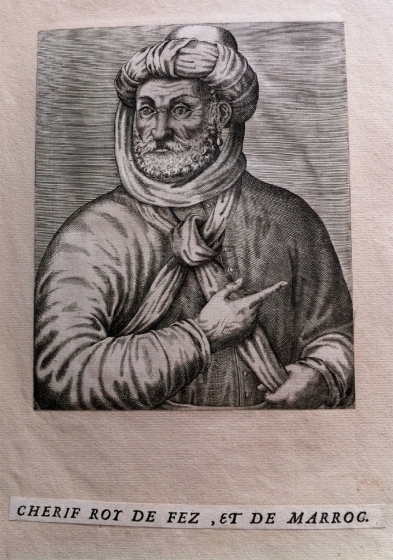

According to Islamic History professor Stephen Cory, the city of Fez was among «the worst hit locations at the time». However, in his book «Reviving the Islamic Caliphate in Early Modern Morocco» (Routledge, 2016), the historian indicates that the plague had ended up reaching Marrakech, al-Mansur’s capital.

al-Mansur's preventive measures

An English report from June 1598 recalls that 230 thousand people died in the city because of the plague. The situation was life-threatening to the Saadi sultan who had to leave Marrakech to avoid contagion.

According to the same record, al-Mansur «abandoned his beautiful palace and ruled from tents in the countryside during the summer months when the plague was at its worst».

While al-Mansur was dwelling in tents, away from the plague, the country was living in complete uncertainty. Quoting English observers, Cory wrote that «merchants traveling to Morocco found the ports to be deserted» and the authorities «were often unreachable due to death or sickness».

Insecurity has paved the way for violence and rumors. «Conditions were so bad that it was rumored that al-Mansur himself had died», the same historian wrote.

«Such a significant weakening of the central government raised the question of Morocco’s vulnerability to outside attacks, and, as a result, there were rumors that Spain or the Ottomans were planning to invade the country during its time of weakness».

Between 1599 and 1601, the plague and its fatalities abated but resumed the next year. In 1602, al-Mansur who left Marrakech to settle political problems sent his son Abou Faris, the governor of the Red city, a letter.

«In his letter, dated September 1, 1602, al-Mansur gave Abou Faris instructions on what he should do if the plague was to reach (again) the gates of Marrakech», Cory wrote. As expected, the plague reinvaded the city, forcing Abou Faris to do as his father did and retreat to live in tents to «minimize the potential of being infected by the plague».

Winning his son and dying of the plague

Meanwhile, the father was leading a different battle against his own son. Forced to leave his tents in the countryside, al-Mansur headed to Fez with his army to fight his son Al-Shaykh who «rebelled against him with the intention of taking his throne», wrote Mercedes García-Arenal in «Ahmad al-Mansur: The Beginnings of Modern Morocco» (Oneworld Publications, Dec 1, 2012).

After al-Mansur sent his ulemas to his son to «convince him to abandon the path of rebellion and to offer the governship of Sijilmassa», he decided to fight him when he refused his offer.

In October 1602, al-Mansur and his army fought the son and won the battle. Although the sultan emerged victorious from his war against his son, his other war against the plague had not ended yet.

Indeed, al-Mansur never returned to his Marrakech palace after traveling to Fez. In the outskirts of the city, which was the most hit by the plague, al-Mansur got infected and died. «He died of the plague while on the outskirts of Fez with his army in August 1603», the historian wrote.

The great ruler who invaded the Songhai empire and defeated a European king, was offered a «very simple ceremony» when he died. He was buried in Fez and later transported to Marrakech, where he is currently buried with his forebears.

And as uncertainty, famine and disease marked the end of his reign, confusion and division marked the period following his death with his two powerful sons forming their own entities, armies and alliances.

chargement...

chargement...