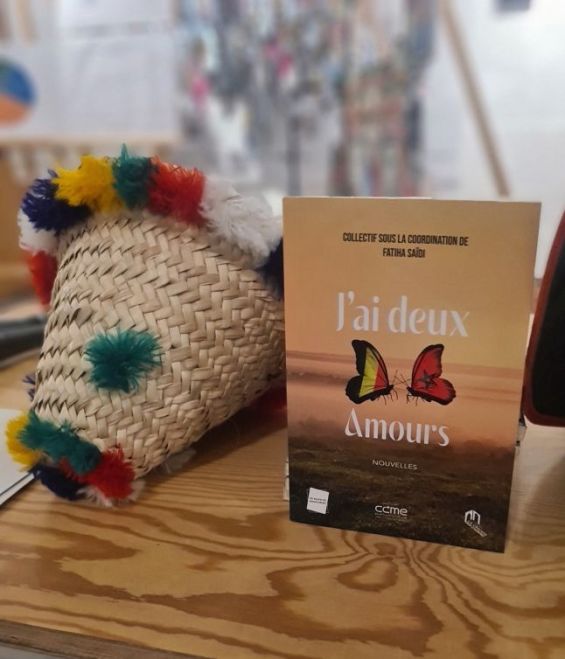

For the first time in 60 years of Belgian-Moroccan immigration, a group of binational authors has come together for a collective writing project exploring both Morocco and Belgium. In the short story collection «J’ai deux amours» (I Have Two Loves), psychopedagogue and gender expert Fatiha Saidi brings together first-generation migrants and writers from subsequent generations to share diverse narratives and perspectives on both countries.

This book serves as a bridge between generations, with its initiator—a political representative from 1999 to 2018—remaining deeply committed to preserving memory. Through a rich tapestry of stories, the collection delves into contemporary challenges in both the country of origin and the country of residence, as well as themes of ancestry, death, childhood memories, the symbolism of land, and social representations.

In this interview, Fatiha Saidi explains how the experiences of today and tomorrow, as lived and recounted by the children of immigrants, are meaningfully reflected in this work.

How did the idea for this project come about ?

This project is close to my heart, and the idea emerged as part of the 60th-anniversary celebrations of Moroccan immigration to Belgium in 2024. The immigration agreements were signed on February 17, 1964. I wanted to leave a lasting mark—a human story capturing the journeys of those shaped by this migration. For me, there is no better way to do that than through a book. Since I am neither a director nor a filmmaker, my medium remains writing.

Later, I thought it would be most interesting to bring together Belgian-Moroccan authors for a collective short story collection. I immediately considered involving my friend Saïd Ben Ali, with whom I was finalizing an epistolary novel, Come Back and Tell Me You Love Me, which was released around the same time. That’s how I Have Two Loves came to life.

Saïd Ben Ali embraced the idea, and together, we began compiling a list of Belgian-Moroccan authors who came to mind. In the end, twelve voices contributed to the book. We had hoped to include binational Flemish writers as well, but unfortunately, we were unable to reach them—underscoring the cultural divide between French- and Dutch-speaking communities, even among Belgian-Moroccans.

Despite this, those we did reach were enthusiastic about being part of the project. Among them was Ikram Maâfi, one of the last to join, whose participation was especially important to me. I first met her at a literary evening focused on the theme of transmission, alongside our friend Rachid Benzine. That night, she read a deeply moving piece in tribute to her father, who is buried in Morocco. Her words left a lasting impression on me.

Later, when I invited her to contribute to the collection, she accepted—and her text now forms part of I Have Two Loves.

This collection brings together authors of different generations, with a near-equal representation of men and women. Was gender parity an important criterion for you?

Yes, ensuring gender balance was essential to me. A slight imbalance wouldn’t have been an issue, but I couldn’t imagine putting together a collection of eleven stories with twelve authors—including sociologist and immigration specialist Nouria Ouali, who wrote the preface—without maintaining some level of parity.

Fatiha Saidi

Fatiha Saidi

It was equally important to me that women were well represented, because history is written with them. Often, they are the invisible or overlooked figures in this history, and I fight every day to bring them out of the shadows.

As for the diversity of age groups, we are still few in the field of writing as Belgian-Moroccans, within the context of this immigration story. We don’t have a large pool of writers, and we focused on those within the Brussels region.

However, I believe this group of authors is fairly representative of our immigration experience, with contributors aged between 30 and 60, including those in their 40s and 50s.

This panel reflects our immigration story, much like what you’ve done previously in Echo of Memory on the Rif Mountains, a tribute to your region of origin. In this new work, do you see it as part of a collective process, similar to your approach of giving a voice to those shaping immigration?

I would say yes and no. Yes, because for a few decades now, I’ve felt it’s essential for us to speak for ourselves. Our parents didn’t write or speak for themselves. By sharing our migratory journeys, we also give them back their voices, as we speak about the paths they walked.

In a way, we’re also recounting their stories. They migrated, settled in a new land, and then Belgium became our country. Some of us were born here, while others, like me, arrived at the age of 5 or 6, like Ahmed Medhoune, one of our authors, or Nouria Ouali.

Moreover, I wouldn’t say this collective project fully aligns with my personal writing approach, as I gave the authors some technical constraints, such as limiting story length and requiring them to evoke both Morocco and Belgium. Beyond that, the stories could take any form, either inspired by real life or entirely fictional, depending on the author’s choice.

My own story is entirely fictional and titled I Have Two Loves, in reference to the song by Joséphine Baker. It explores the journey of a young woman questioning her dual identities. I drew inspiration from Amin Maalouf’s book Deadly Identities as I crafted my narrative.

Taha Adnan also contributed a fictional story, while Ahmed Medhoune told the story of a little boy, which seems to reflect his own experience, though it may also be fictional.

Other stories are grounded in real-life writing, such as Ikram Maâfi’s and Fatima Zibouh’s. Fatima, for example, wrote a letter to her son with an autobiographical narrative.

Faten Wehbe offered a fictional tale about a young couple facing racism in Belgium, who, after deciding to return to Morocco, realize that the country they idealized no longer feels familiar. They have to confront society again and «integrate» once more.

These are unique and varied stories, each with its own personal style.

Returning to your story and the title of the collection, why Joséphine Baker? What does she represent to you?

Joséphine Baker is someone very dear to my heart. I admire her not only for her artistic talent but also for her commitment and activism. She embodied an open, world-embracing figure, and I appreciate her willingness to welcome children from the countries she visited, including a Moroccan child.

Joséphine Baker

Joséphine Baker

Joséphine Baker was also deeply engaged during World War II, and I particularly admire her fight against racism. The concept of «two loves» is perfect for a collection of stories like the one we’re creating, which explores both Belgium and Morocco. In her song, she sings about America and France—two countries where she struggled—but she praises them as her loves, even when they were difficult.

Given my deep admiration for Joséphine Baker, I read extensively about her and discovered that she had once visited Morocco, though unfortunately under less-than-ideal circumstances. She was ill, hospitalized, and taken under the protection of King Mohammed V. I found this history particularly symbolic for our choice of title.

In a world where racist discourse is on the rise, where colonization is being legitimized, and xenophobic political currents are gaining momentum, is your reference to Joséphine Baker a way of showing that the struggles of the past are still relevant today?

I think that’s exactly what it reflects, and this kind of racism is present in some of the stories. Joséphine Baker fought against racism, and unfortunately, it’s still very much alive today. It’s even growing stronger, with nationalism rising in ways that could take us back to parts of history we never want to revisit.

The world today is incredibly frightening, and it's not just Europe. When we look at what’s coming out of America, we don’t feel reassured either. A book like this, through its short stories, can highlight how many people are still stigmatized, even after living in a country for decades. They are often still assigned a residence, but which residence is truly theirs?

What does «residence» mean for an individual? Is it the country where they were born, or the country where they’ve lived for over fifty years? These are the questions and stories that transcend our narratives.

Preface: Nouria Ouali

Authors: Taha Adnan, Saïd Ben Ali, Mohamed Rayane Bensaghir, Souad Fila, Mustapha Haddioui, Ikram Maâfi, Abdeslam Manza, Ahmed Medhoune, Fatiha Saïdi, Faten Wehbe, and Fatima Zibouh.

chargement...

chargement...